Mocking HTTP Services in Rust

How to simulate external HTTP services for automated tests and prototyping

At some point, most developers needed to test applications that interact with external HTTP services, such as third-party APIs, authentication providers, or data sources. These services are not always available to us, especially during automated tests or when prototyping a new service. To verify that our applications use these APIs as expected, we need tools that allow us to verify outgoing requests and to mimic API responses tailored to our use cases and test scenarios. This is where mocking libraries can help.

HTTP mocking libraries usually allow you to create an HTTP server and configure it for custom request/response scenarios. While most libraries provide the functionality to mock HTTP servers in automated tests, some also give you the possibility to run a configurable standalone server application that mimics APIs for multiple applications at once. This article shows how we can use such tools to mock HTTP services in Rust.

The App

Let's suppose we are building a Rust application that will create a GitHub repository on our behalf. To perform these operations, we will use the GitHub REST API. We will then write some automated tests to verify correct behavior by simulating HTTP responses from GitHub.

Let's start!

Let's first create a new cargo package for our app and name it github_api_client:

cargo new github_api_client --bin

We'll also need some libraries, so let's add them to our dependency list. We'll use

isahcas our HTTP client library,serde_jsonfor easy JSON serialization and deserialization, andcustom_errorto create custom error types.

Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

isahc = { version = "1.6", features = ["json"]}

serde_json = "1.0"

anyhow = "1.0"

The Client

Now let's add the following code that will allow us to access the GitHub REST API. We will create a structure named GithubClient that will contain all the logic required to access the GitHub API.

main.rs:

use isahc::{ReadResponseExt, Request, RequestExt};

use serde_json::{json, Value};

use anyhow::{Result,ensure};

pub struct GithubClient {

base_url: String,

token: String,

}

impl GithubClient {

pub fn new(token: &str, base_url: &str) -> GithubClient {

GithubClient { base_url: base_url.into(), token: token.into() }

}

pub fn create_repo(&self, name: &str) -> Result<String> {

let mut response = Request::post(format!("{}/user/repos", self.base_url))

.header("Authorization", format!("token {}", self.token))

.header("Content-Type", "application/json")

.body(json!({ "name": name, "private": true }).to_string())?

.send()?;

let json_body: Value = response.json()?;

ensure!(response.status().as_u16() == 201, "Unexpected status code");

ensure!(json_body["html_url"].is_string(), "Missing html_url in response");

return Ok(json_body["html_url"].as_str().unwrap().into());

}

}

fn main() {

let github = GithubClient::new("<github-token>", "https://api.github.com");

let url = github.create_repo("myRepo").expect("Cannot create repo");

println!("Repo URL: {}", url);

}

The only method our client currently provides is create_repo. It takes the repository name as an argument and returns a Result containing the repository URL as a string value. To keep this example simple, we use the anyhow crate for generic error handling.

The Problem

Now that we have a functional app, we want to write some tests to make sure it doesn't have any obvious problems.

One tricky part is to find a suitable target for mocking so that we can test the behavior of our client in different situations. In our case, the HTTP clients Request::post function looks like a good place to start because it's the last function that our GitHub client calls before it sends a request to the GitHub API servers.

Unfortunately, mocking HTTP clients is not very practical if there is no dedicated mocking library for your particular HTTP client. This is because, in a larger application, we would need to reimplement a big part of the HTTP client’s API to be able to adequately simulate request/response scenarios. So what to do?

The Solution

To test our GitHub API client conveniently, we can use an HTTP mocking library. Such libraries can help us with at least two testing targets:

- Verifying that all HTTP requests our client sends are correct (i.e., contain all expected values).

- Simulating HTTP responses from the GitHub API to see if our client can deal with them accordingly.

At the time of writing there are at least the following Rust libraries that can help us with this:

mockitohttpmockhttptestwiremock.

The following comparison matrix shows how the libraries compare to each other:

| Library | Execution | Custom Matchers | Mockable APIs | Sync API | Async API | Stand-alone Mode |

| mockito | serial | no | 1 | yes | no | no |

| httpmock | parallel | yes | ∞ | yes | yes | yes |

| httptest | parallel | yes | ∞ | yes | no | no |

| wiremock | parallel | yes | ∞ | no | yes | no |

According to the comparison matrix, the most complete package is currently provided by httpmock. For this reason, we will use this one for the rest of this article (and because the author is the creator of httpmock 😛). Although we will use httpmock, you can also find most of the presented features in any of the other libraries as well.

Creating Mocks

In this section, we'll write some tests to verify that our GitHub API client works as expected. Let’s first add the httpmock crate to our dependencies:

Cargo.toml:

[dev-dependencies]

httpmock = "0.6"

Now we’re all set. Let’s create a test that will make sure the "good path" in our client implementation works as expected:

main.rs:

// ...

1 #[cfg(test)]

2 mod tests {

3 use crate::GithubClient;

4 use httpmock::MockServer;

5 use serde_json::json;

6

7 #[test]

8 fn create_repo_success_test() {

9 // Arrange

10 let server = MockServer::start();

11 let mock = server.mock(|when, then| {

12 when.method("POST")

13 .path("/user/repos")

14 .header("Authorization", "token TOKEN")

15 .header("Content-Type", "application/json");

16 then.status(201)

17 .json_body(json!({ "html_url": "http://example.com" }));

18 });

19 let client = GithubClient::new("TOKEN", &server.base_url());

20

21 // Act

22 let result = client.create_repo("myRepo");

23

24 // Assert

25 mock.assert();

26 assert_eq!(result.is_ok(), true);

27 assert_eq!(result.unwrap(), "http://example.com");

28 }

39 }

We arranged the test code following the AAA (Arrange-Act-Assert) pattern, which divides the test into three parts: Arrange, Act, and Assert.

Arrange

The first thing we do in our test is to create a MockServer instance (line 10) which we then use to create a Mock object with

- all values that the

MockServershould expect from an incoming HTTP request (lines12–15), and - a specification for HTTP responses that will be sent back should any incoming HTTP request match all expected values (lines

16–17).

Notice how we used the when variable to define request expectations and the then variable to specify response values.

The mock server will only respond if it receives an HTTP request that meets all expectations. Otherwise, it will respond with an error message and HTTP status code 404.

Important: Observe how we set the base URL in our client to point to the mock server instead of the real GitHub API (line 19).

Act

In this part, we execute our code under test (line 22) which is the method create_repo of our GithubClient.

Assert

At last, we use the assert method provided by the Mock object (line 25). This method makes sure that the mock server received exactly one HTTP request that matched all expectations. If not, it will fail the test and print a detailed problem description (see next section).

Debugging

Mock objects provide an assert method that ensures that our application has sent a request to the mock server that matched all expectations (the when). If not, this method will fail the test. In this case, httpmock will try to find a request in its request journal that is most similar to your mock expectations. It will then identify the differences between the two, so you can easily spot incorrect or missing values.

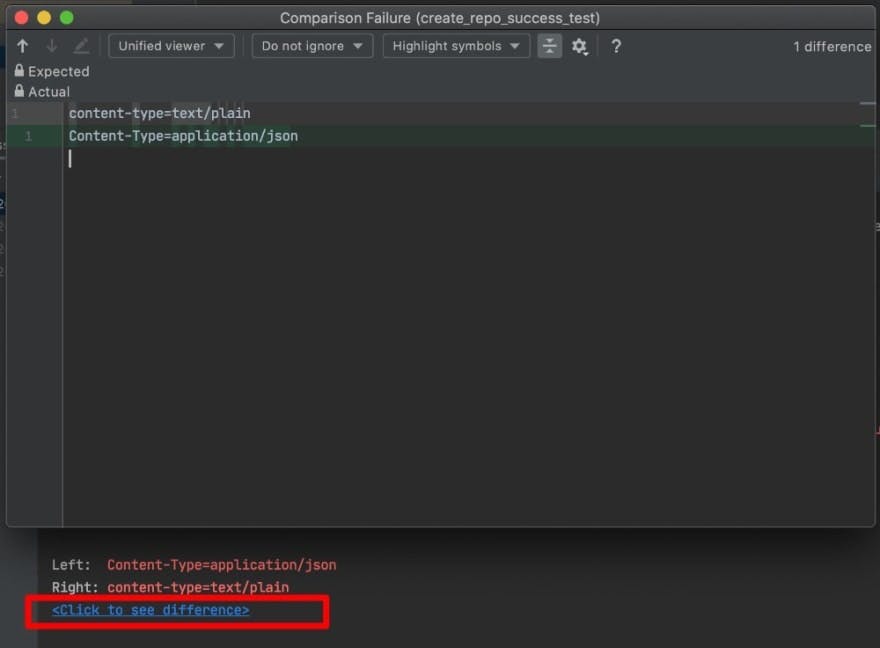

To demonstrate this feature, we will modify our client to send text/plain in the content-type header instead of application/json. If we then rerun the test, we'll see that this change is detected, and the test fails now with the following message:

At least one request has been received, but none exactly matched the mock specification.

Here is a comparison with the most similar request (request number 1):

1 : Expected header with name 'Content-Type' and value 'application/json' to be present in the request but it wasn't.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Expected: [key=equals, value=equals] Content-Type=application/json

Actual (closest match): content-type=text/plain

Depending on your IDE, you will also be able to see the differences between the expected and the actual value in a differences viewer. For example, this is how it would look like in IntelliJ or CLion:

Standalone Mock Servers

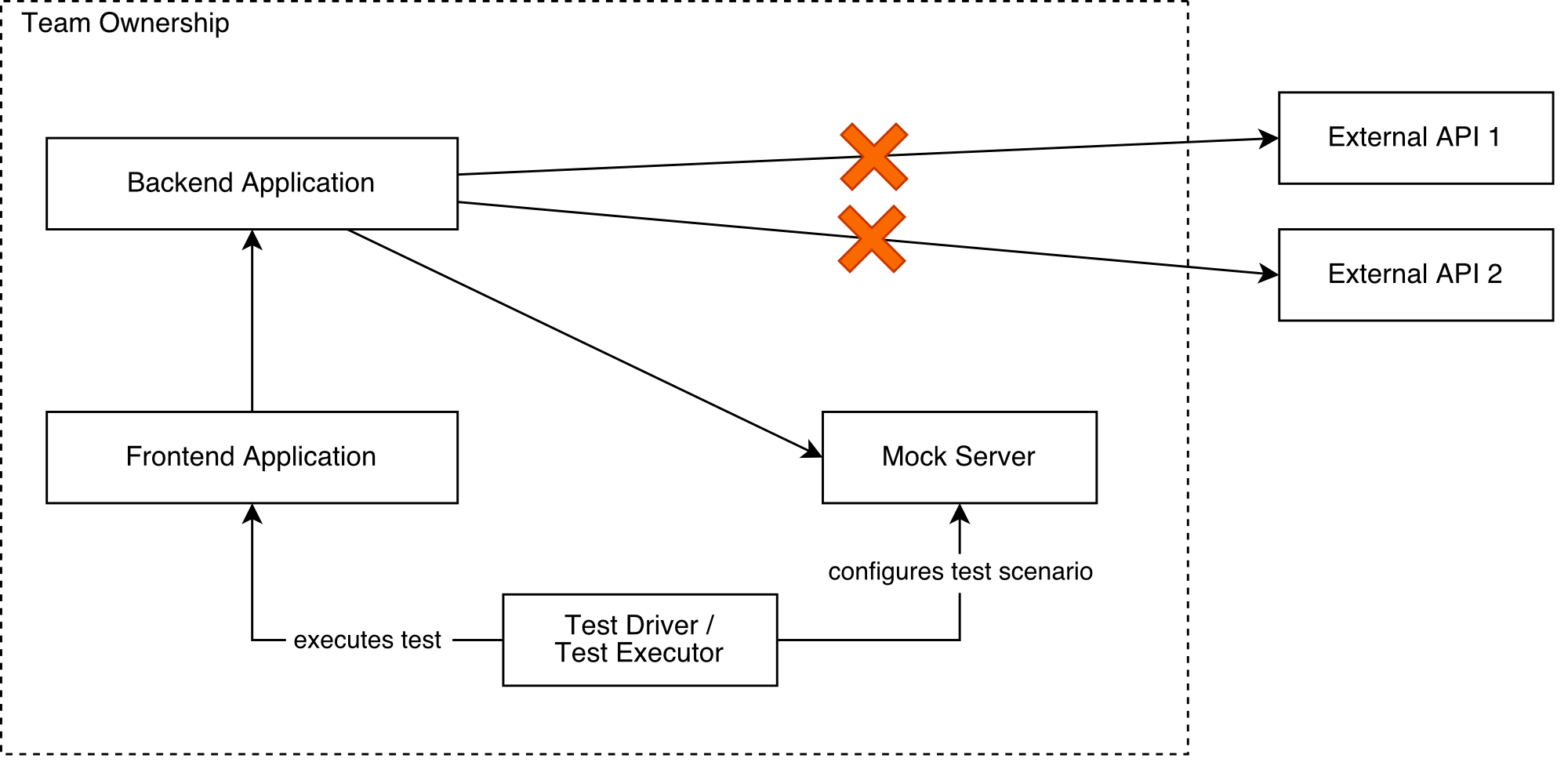

Until now we only looked at mocking external HTTP services in integration tests, which typically run in the context of one application. End-to-end tests, on the other hand, may involve more than one application. In this case, multiple applications may need access to external HTTP services, while some of them may not be easily available for tests. Especially in early development stages or during prototyping, chances are that some services are still under development and not yet ready to use.

When multiple applications need access to a mocked API, it is practical to have a dedicated mock server running in a separate process that provides mocked APIs to multiple applications. This allows the test executor to configure the mock server to behave differently for every test scenario.

Some mocking libraries come with an optional standalone mock server. Others may have third-party extensions or community projects that extend the library with a standalone mock server.

For example, httpmock comes with a separate Docker image that lets you run a dedicated mock server. We can use it in the following ways:

- Dynamic configuration using Rust: The end-to-end test executor is a Rust test that uses

httpmockin almost the same way as presented in our integration tests earlier. The only difference is that it connects to a remote mock server (e.g., by usingMockServer::connect) instead of creating a local mock server instance (e.g., by usingMockServer::start). In this case, all test functions that connect to the server are automatically executed sequentially to avoid conflicts. - Static YAML file configuration: This mode allows you to set up a mock server with a static configuration that does not need to change. This approach does not require any test execution or Rust program. Instead, the mock server reads its configuration from YAML mock definition files, which are very similar in structure to the Rust API (see example here).

Optionally, both modes can be mixed. Please refer to the httpmock documentation for more information on the standalone mode.

Conclusion

This article showed how we can use a mocking librariy to simulate HTTP services. We have seen how it allowed us to verify that our application was sending HTTP requests that matched our expectations during automated tests. We could also simulate HTTP responses from the GitHub API to make sure that our app can process them accordingly. Furthermore, it was shown how mocking tools can also be used to replace unavailable HTTP services during development and make them accesible to many applications at once.

Versatile mocking tools can be practical in multiple stages of the development lifecycle, not just integration tests. However, they are especially useful for hardening our HTTP-based API clients and allow us to test for edge cases that would otherwise be hard to reproduce.